September 1, 2019

Here you will find the material for the introductory workshop held at Notam, Oslo in late summer 2019.

The slides may be used as a sort of cheatsheet as well as notes for remembering the topics covered:

• An overview: What is SuperCollider and what can you do with it?

• The design and architecture of SuperCollider

• Language basics: syntax, variables, expressions and functions

• Learning resources: How to proceed from here

about me

Who am I?

- Mads Kjeldgaard

- Composer & developer

- Work at NOTAM

Contact info

- website: madskjeldgaard.dk

- github: github.com/madskjeldgaard

- email: mail@madskjeldgaard.dk

Design

Short history of SuperCollider

SC was designed by James McCartney as closed source proprietary software

Version 1 came out in 1996 based on a Max object called Pyrite. Cost 250$+shipping and could only run on PowerMacs.

Became free open source software in 2002 and is now cross platform.

Overview

When you download SuperCollider, you get an application that consists of 3 separate programs:

- The IDE, a smart text editor

- The SuperCollider language (sclang)

- The SuperCollider sound server (scsynth)

Architecture

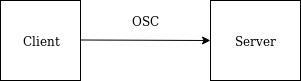

The client (language and interpreter) communicates with the server (signal processing)

This happens over the network using Open Sound Control

Multiple servers

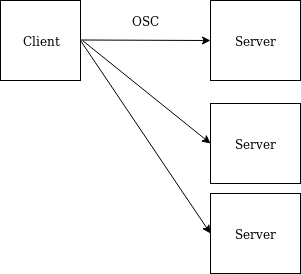

This modular / networked design means one client can control many servers

Consequences of this modular design

Each of SuperCollider’s components are replacable

IDE <—> Atom, Vim, or Visual Studio

language <—> Python, CLisp, Javascript

server <—> Max/MSP, Ableton Live, Reaper

Syntax, strings and variables

Hello world

Use .postln to post something to the post window (important when

debugging):

"Hello world".postln

An important point on numbers in SC

As opposed to mathematical convention: there is no hierarchy between operators

If you pick up a calculator and type 2+2*10 the result is probably

=22

Because normally there is an implicit parenthesis here: 2+(2*10).

This isn’t the case in SuperCollider:

2+2*10

-> 40

Using brackets to create mathematical hiararchy

SC looks at the first part (2+2) and calculates it, then multiplies it

(*10).

Therefore: Always use parenthesis when you need mathematical hierarchy:

2+(2*10)

-> 22

Syntax

Like with any other programming language, correct syntax is important.

When you get it wrong, the interpreter will give you an error (and thus help you solve your problem)

If for example I wanted to write 9.cubed but accidentally wrote

9cubed and evaluated it, I would get the following error

RECEIVER: nil

ERROR: syntax error, unexpected NAME, expecting $end

in interpreted text

line 1 char 6:

9cubed

^^^^^

-----------------------------------

ERROR: Command line parse failed

-> nil

Brackets / parenthesis

() encapsulates a block of code that is supposed to be executed

together ; is used to mark the end of a statement

An example of a block:

(

a = 111+222+333;

b = 444+555+666;

c = 777+888+999;

)

a; // -> 666

b; // -> 1665

c; // -> 2664

Expressions

The end of an expression is marked by a semicolon ;

SC will interpret everything up until the semicolon as one expression

Example: Two expressions

"hello".postln; "how are you?".postln;

This results in the following in the post window:

hello

how are you?

-> how are you?

Receiver notation

A way of executing a function (message) on an object (receiver)

Receiver.message(argument)

or

message(Receiver, argument)

Examples:

100.rand same thing as rand(100)

"hello".postln same thing as postln("hello")

0.123.round(0.1) same thing as round(0.123, 0.1)

The interpreter doesn’t care about line breaks

(

a = [1,2,3,4];

)

Is the same as this:

(

a = [

1,

2,

3,

4

];

)

As long as you use semicolons at the end of your expressions

Comments

// can be used as single line comments:

// This comment is a one line comment Or at the end of a line:

10+10; // This comment is at the end of a line

/* */ is used for multiline comments. Everything between these is

treated as a comment.

/*

Roses are red

Violets are blue

SuperCollider is cool

and so are you

*/

Strings

A string is marked by double quotes: "This is a string";

It is now a String object:

"This is a string".class

-> String

String concatenation

A common string operation is the concatenation of strings

This is done using the ++ operator:

"One" ++ "Two" ++ "Three";

-> OneTwoThree

Symbols

A symbol can be written by surrounding characters by single quotes (may include whitespace):

'foo bar'

Or by a preceding backslash (then it may not include whitespace):

\foo

Why symbols

From the Symbol help file: "A symbol, like a String, is a sequence of characters.

Unlike strings, two symbols with exactly the same characters will be the exact same object."

Symbols are most often used to name things (like synthesizers, parameters or patterns)

Tip: Use symbols to name things, use strings for input and output.

Variables

A variable is a container that you can store data in:

var niceNumber = 123456789;

Variable names

Variable names must be written with a lowercase first letter.

Like this: var thisWorks and not like this: var ThisDoesNotWork

Reserved keywords

Another limitation in naming variables: Reserved keywords

These are words used to identify specific things in SC: nil, var,

arg, false, true

Example:

var var

-> nil

ERROR: syntax error, unexpected VAR,

expecting NAME or WHILE

in interpreted text

line 1 char 7:

var var

^^^

Local variables

Local to a block of code

Must be initialized at the top of the block

Environment variables

“Global” in scope, can be accessed throughout the environment

Don’t need a var keyword in front of them when declared

Can be initiliazed at any point in the program

Writing environment variables

The letters a-z:

a = [1,2,3,4,5,6]The tilde (~) prefix

~array = [1,2,3,4,5,6]

Demonstration of variable scope

(

// local variable

var array = [1,2,3];

// This works:

array.postln;

)

// This returns a "not defined" error:

array.postln;

When to use local variables

Use local variables as often as possible

For example when designing a system, writing the insides of functions, etc.

This will keep your code clean and make it easier for you to maintain

When to use environment variables

Use environment variables for interactive coding

For example when prototyping or live coding

Syntax shortcuts

SC allows the user to write code in different styles using different types of syntax.

The helpfiles “Syntax Shortcuts” and “Symbolic Notation” can be a big help when this becomes confusing

Functions

What is a function?

A function is a reusable encapsulation of functionality

Lets you reuse and call it elsewhere in your code

Repetitive code can often be simplified with functions

Functions

The core of the function is contained in curly brackets: {}

We declare a function like this. Note: This does not evaluate or activate the function yet:

{2+2}

-> a Function

A function is evaluated by sending it the .value message:

{2+2}.value

-> 4

Syntactic sugar

Tip: .value can be omitted by just adding .() like so:

{arg x, y; x+y}.(x:2, y:7), although .value is usually clearer

Function arguments

Functions can take arguments (data) as input and do something with them.

Arguments must be declared in the beginning of the function.

To pass values to the arguments, open a parenthesis after .value

Here we have named the argument x

{arg x; 2+x}.value(x: 8)

-> 10

Alternatively, the argument name can be omitted (but then you have to know the order of arguments):

{arg x, y; x+y}.value(2, 8)

-> 10

Named

You can call arguments by their names:

{arg x, y; x+y}.value(x:2, y:8)

-> 10

Mixing named and unnamed arguments

You can mix named and unnamed arguments but you must call the unnamed arguments at the end of the list

correct way:

{arg x=2, y; x+y}.value(2, y:8)

-> 10

incorrect way:

{arg x=2, y; x+y}.value(x:2, 8)

ERROR: syntax error, unexpected INTEGER, expecting ')' in interpreted text

Alternative argument syntax

Instead of writing arg argname1, argname2 you can put the arguments

inside pipe symbols:

f = {|x, y| x+y}

Argument default values

You can set the initial value of an argument when declaring it:

f = {|x=1, y=4| x+y}

Declaring multiple arguments or variables in one go

You can choose between declaring like this:

arg argument1, argument2, argument3;

Or like this:

arg argument1;

arg argument2;

arg argument3;

The same goes for local variables

Functions can be put in variables and reused

f = {arg x, y; x + y};

f.value(2,1000); // = 1002

f.value(9,22); // = 31

Function returns

All blocks of code in SC return the result of the last statement (in

both () and {})

This is useful for doing further computations

f = {arg x, y; x + y};

a = f.value(2,1000); // = 1002

b = f.value(9,22); // = 31

a+b; // = 1033

Learning resources

Videos

Tutorials by Eli Fieldsteel covering a range of subjects: - SuperCollider Tutorials

James McCartney (author of SuperCollider) giving a talk at IRCAM: - SuperCollider and Time

Books

- Introduction to SuperCollider - Written by Andrea Valle, includes pdf. Published 2016.

- The SuperCollider Book – The essential reference. Edited by Scott Wilson, David Cottle and Nick Collins. Foreword by James McCartney. Published 2011.

- Thor Magnussons Scoring Sound - Cookbook containing synthesis recipes among other things

- Mapping and Visualization with SuperCollider - Create interactive and repsonsive audio-visual applications with SuperCollider

Community

Awesome SuperCollider

A curated list of SuperCollider stuff

Find inspiration and more resources here:

#workshop-material #supercollider